Into the Valley of Roses

How Bulgaria built a national symbol around the rose – and why it might lose it.

HUDDLED BETWEEN THE SOARING BALKAN MOUNTAIN MASSIF and the lower, smoother curves of the Sredna Gora ridge, fields stretch out far into the distance. It is late May, rose harvest season in central Bulgaria. The previous afternoon, we – a Bulgarian journalist and an American photographer – drove east from the capital, Sofia, to observe the rose harvest and rose festival celebrations. As the dawn sky slowly turns from black to a deep dusty blue, sunlight peeks out from behind the mountains and the first light of the day reveals row upon row of rose bushes. Just visible through the mist, we can make out the shadows of workers, moving methodically as they grasp and pluck, grasp and pluck, filling their bags with handfuls of dew-covered flowers.

This harvest produces one of Bulgaria’s most precious commodities. The unique microclimate of this pristine valley provides ideal conditions for the Rosa Damascena – the “Rose of Damascus” – an ode to its probable origins. In the late spring, their petals produce one of the world’s most sought-after and expensive essential oils.

Many have tried to replicate these conditions elsewhere – from Romania to France to China – but none rival the Rose Valley. The genus requires conditions that are as fickle as they are precise. Only the combination of fertile soil watered by the spring that flows from the nearby mountain, and the specific levels of humidity and heat that exist here for a few short weeks in May and June, will satisfy it and produce such exquisite-smelling and productive yields.

As the sun rises, the dew that has gathered on the flowers begins to warm and a sweet fragrance wafts up through the air. “It’s roses, roses all the way,” the jubilant narrator from a British Pathé film exclaimed in a 1965 reel about Bulgaria. “The Valley of Roses: there is no other rosy valley like this in the whole wide world.”

THE ROSE VALLEY stretches from the historic rebel town of Karlovo in the west, birthplace of Bulgarian revolutionary hero Vasil Levski who led the rebellion against Ottoman rule, to Kazanlak in the east, an industrial centre known for manufacturing Kalashnikov assault rifles. In a country that ranks among the poorest of the European Union’s member states, these two long-standing exports – guns and roses – have made Bulgaria’s Rose Valley one of the country’s wealthiest regions.

Rose essential oil (known as otto or attar) is the distilled essence of rose petals and an essential ingredient in many of the world’s most exclusive perfumes and cosmetics, as well as spa treatments, pharmaceuticals, foods, and aromatherapies. It is expensive and time consuming to produce, but the potential profits can far outweigh the initial costs. In 2018, the global rose oil market was worth $278.7 million and was on track to expand, according to a market analysis report.

Often nicknamed “Bulgarian gold”, the market rate has at times reached €12,000 per kilo, and Bulgaria – a country of just seven million people – is the world’s most important producer. Rose oil exports make up only a fraction of the country’s total essential oil production – Bulgaria recently overtook France as the top producer of lavender oil – but the symbolic importance of the Bulgarian rose industry has always meant at least as much to the country and its people as the economic benefits it brings.

In 1903 the city of Kazanlak organised its first Rose Festival, an annual event which grew to national significance when a railway line connected the city to the capital Sofia in the 1930s. The Rose of Damascus was made the national brand of the country under the Bulgarian Communist Party, and the Bulgarian rose industry continues to thrive today as both a prized export sent out to other countries and as a cultural attraction drawing in visitors.

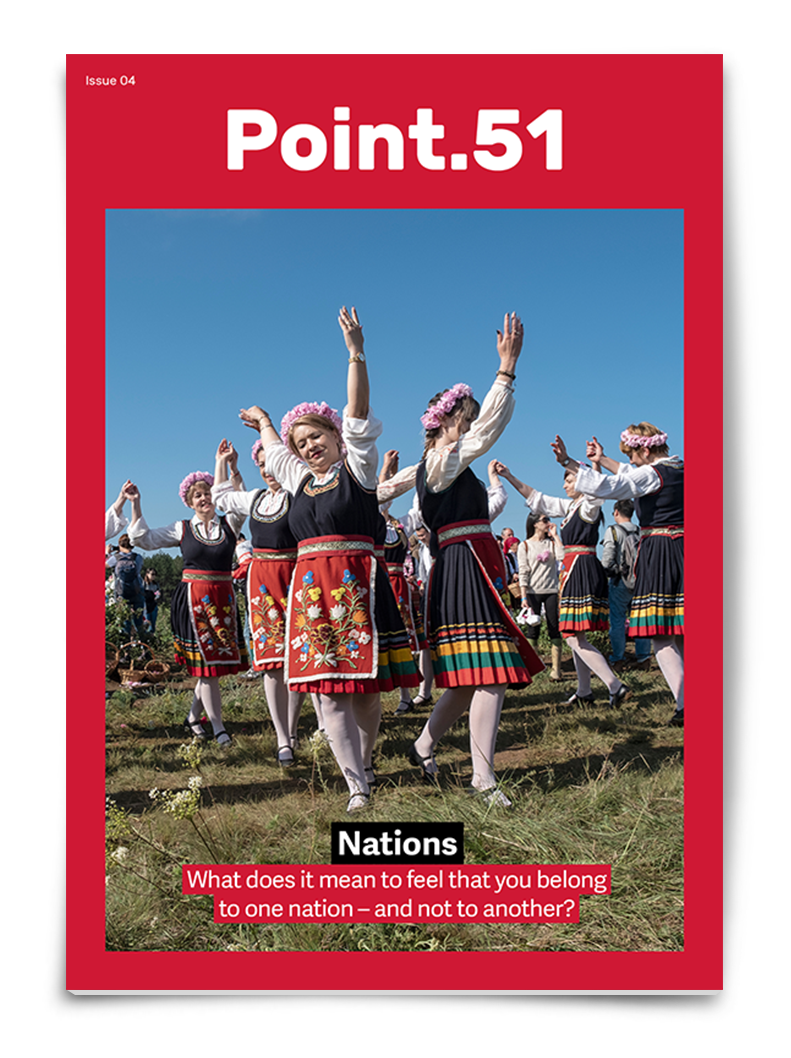

The annual rose festival, which includes a “carnival” parade, exhibitions and performances, culminates with the procession and coronation of the Rose Queen and draws tourists from across Bulgaria and around the world. Local women, wearing colourful folk dresses, re-enact the traditional harvest: they pluck roses and fill their handwoven baskets, occasionally flinging petals in the air to the delight of photo-snapping spectators. Their pointed-toe pigskin shoes daintily brush against the soft earth as they perform a traditional horo dance against a backdrop of rose bushes. Sturdy-looking men wearing embroidered shirts and woolly hats called kalpak collect the women and their harvest in the back of a horse-drawn cart, and together they travel a short distance to an antique fire-powered distillery to demonstrate the distillation process.

The prominence of the rose in Bulgaria reaches well beyond the rose valley itself. Most Bulgarian souvenir shops sell all manner of rose products: tiny wooden vials of rose oil, bottles of clear rose water, shockingly pink bars of rose petal soaps, rose-oil creams and rosewater lotion, and postcards showing fair-skinned, traditionally-dressed Bulgarian women posing in rose fields. Missing from the postcards are the agricultural workers who make all this possible. There is a saying in Bulgaria: “Nyama roza bez bodli”. There’s no rose without thorns.