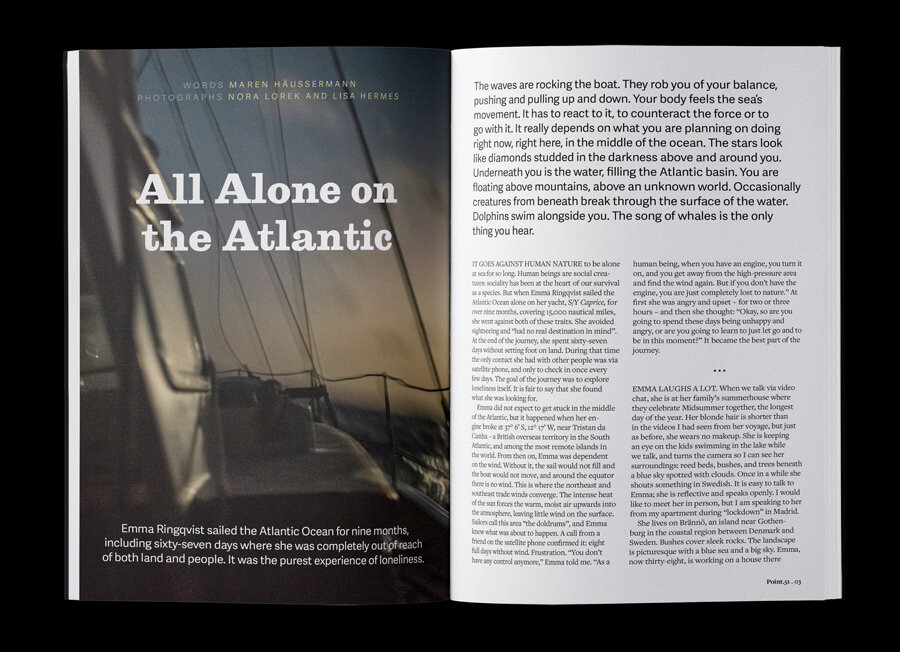

All Alone on the Atlantic

Emma Ringqvist sailed the Atlantic Ocean for nine months, including sixty-seven days where she was completely out of reach of both land and people. It was the purest experience of loneliness.

The waves are rocking the boat. They rob you of your balance, pushing and pulling up and down. Your body feels the sea’s movement. It has to react to it, to counteract the force or to go with it. It really depends on what you are planning on doing right now, right here, in the middle of the ocean. The stars look like diamonds studded in the darkness above and around you. Underneath you is the water, filling the Atlantic basin. You are floating above mountains, above an unknown world. Occasionally creatures from beneath break through the surface of the water. Dolphins swim alongside you. The song of whales is the only thing you hear.

It goes against human nature to be alone at sea for so long. Human beings are social creatures: sociality has been at the heart of our survival as a species. But when Emma Ringqvist sailed the Atlantic Ocean alone on her yacht, S/Y Caprice, for over nine months, covering 15,000 nautical miles, she went against both of these traits. She avoided sightseeing and “had no real destination in mind”. At the end of the journey, she spent sixty-seven days without setting foot on land. During that time the only contact she had with other people was via satellite phone, and only to check in once every few days. The goal of the journey was to explore loneliness itself. It is fair to say that she found what she was looking for.

Emma did not expect to get stuck in the middle of the Atlantic, but it happened when her engine broke at 37° 6’ S, 12° 17’ W, near Tristan da Cunha – a British overseas territory in the South Atlantic, and among the most remote islands in the world. From then on, Emma was dependent on the wind. Without it, the sail would not fill and the boat would not move, and around the equator there is no wind. This is where the northeast and southeast trade winds converge. The intense heat of the sun forces the warm, moist air upwards into the atmosphere, leaving little wind on the surface. Sailors call this area “the doldrums”, and Emma knew what was about to happen. A call from a friend on the satellite phone confirmed it: eight full days without wind. Frustration. “You don’t have any control anymore,” Emma told me. “As a human being, when you have an engine, you turn it on, and you get away from the high-pressure area and find the wind again. But if you don’t have the engine, you are just completely lost to nature.” At first she was angry and upset – for two or three hours – and then she thought: “Okay, so are you going to spend these days being unhappy and angry, or are you going to learn to just let go and to be in this moment?” It became the best part of the journey.

Brännö, the island near Gothenburg where Emma now lives. Photographs: Nora Lorek

Emma laughs a lot. When we talk via video chat, she is at her family’s summerhouse where they celebrate Midsummer together, the longest day of the year. Her blonde hair is shorter than in the videos I had seen from her voyage, but just as before, she wears no makeup. She is keeping an eye on the kids swimming in the lake while we talk, and turns the camera so I can see her surroundings: reed beds, bushes, and trees beneath a blue sky spotted with clouds. Once in a while she shouts something in Swedish. It is easy to talk to Emma; she is reflective and speaks openly. I would like to meet her in person, but I am speaking to her from my apartment during “lockdown” in Madrid.

She lives on Brännö, an island near Gothenburg in the coastal region between Denmark and Sweden. Bushes cover sleek rocks. The landscape is picturesque with a blue sea and a big sky. Emma, now thirty-eight, is working on a house there with her partner. It is the next step in her journey: to settle down and live the family life. “It is not always easy,” she says with a laugh. Being alone and having the space for herself has been hard to find lately. When she is not renovating the house and spending time with family, she works in an eco-village that takes care of people with autism. She spends a week there each month caring for the residents, which she loves. A “regular” nine-to-five job is not for her, she explains.

When she was nineteen, Emma moved to London to study music and eventually got stuck there. She found work as a musician, a guitar teacher, and in a music venue; but also in offices, bars, and cafés. For a while, she lived in an abandoned pub with a music studio in the basement. “We used to have great parties”, she says, recalling those days with a smile. Then, after thirteen years, she decided to fulfil one of her dreams: she bought a canal boat. For her last five years in London, she lived on Miss Behavin, a seventeen-metre blue houseboat. Emma would drive her up and down the section of Regent’s Canal in North London known as Little Venice. In the warmer summer months, the surface of the water would become carpeted bank-to-bank with bright green algae. Swans and ducks would swim past the windows, making it feel a bit like she was living in the countryside, in the middle of London.

Emma playing one of her ukaleles while Caprice was anchored in Las Palmas. Two sisters from Germany lived on the boat with her during the time she spent in the Canary Islands. Photo: Lisa Hermes

Houseboats extended along the banks of the canal in long lines, each painted a different colour. Looking out from one of the portholes, Emma could see the rows of townhouses on the streets that run alongside the canal. Front gardens led up to wooden doors flanked by ornate columns, and big rectangular windows held family life behind them. If those inside looked back, they would see their floating neighbours through the trees that surround the water. Then every fourteen days, the neighbourhood changed. Boat tenants have to change their mooring in order to keep their licence. “You practically choose your neighbours. It’s like living in a community but without owning a house together,” Emma explains. They cooked dinner together and helped each other out. “It was like a fairy tale. You have all those little canal boats, and when you walk past them at night, you see candlelight and people sat outside having a drink. It’s really like a dream world.”

But after a while, Emma wanted to be closer to her family and brothers again, and she longed to live by the sea. The sea runs in her blood. She learned how to sail when she was ten, and has had several boats since then, gathering a wealth of experience in handling them. When she turned thirty-seven, she decided it was time to move out of Miss Behavin and head back to Sweden. Emma makes lots of plans, and more often than not, they happen. Before “settling down” on land and perhaps starting a family, she wanted to sail on the open sea once more – for a long time, and all alone.

We hope you’re enjoying this article. You’ve read 1,186 of 4,530 words.

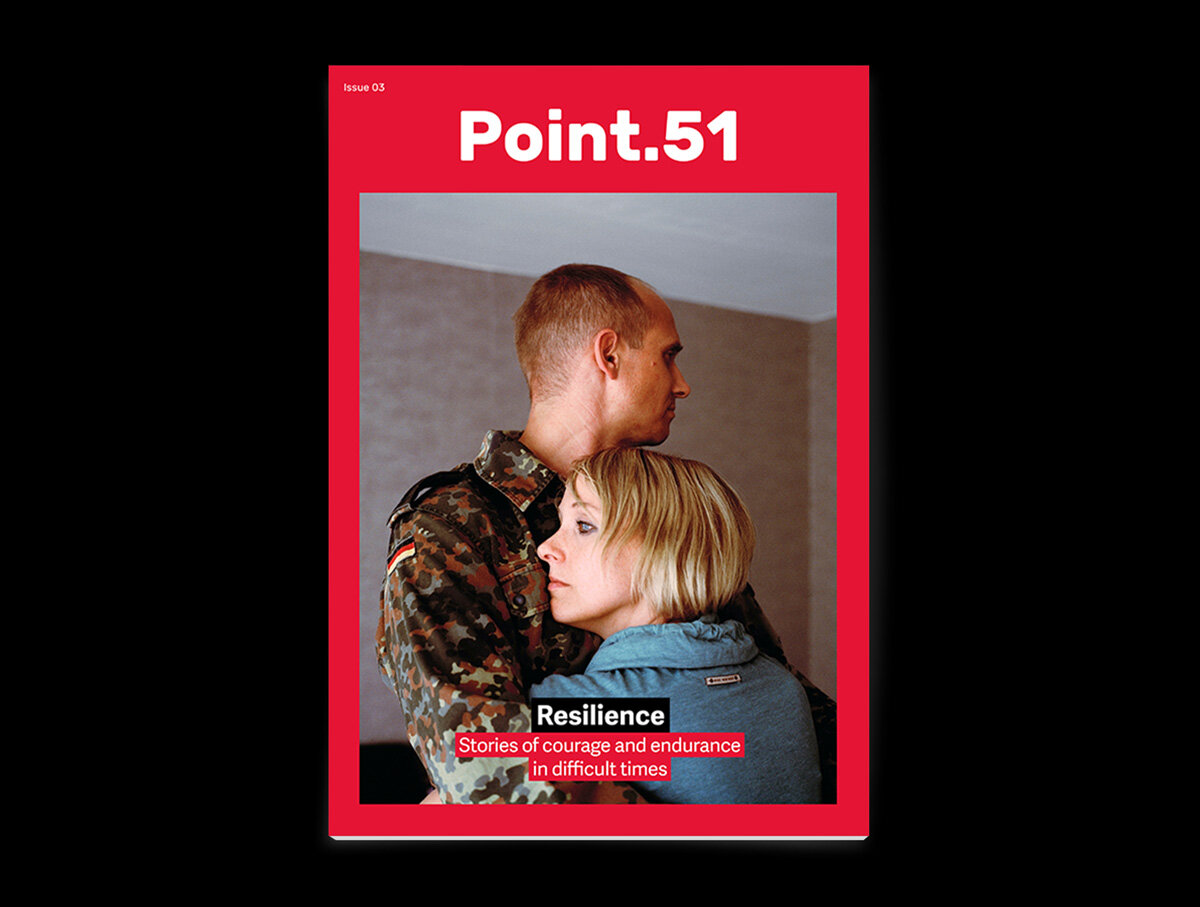

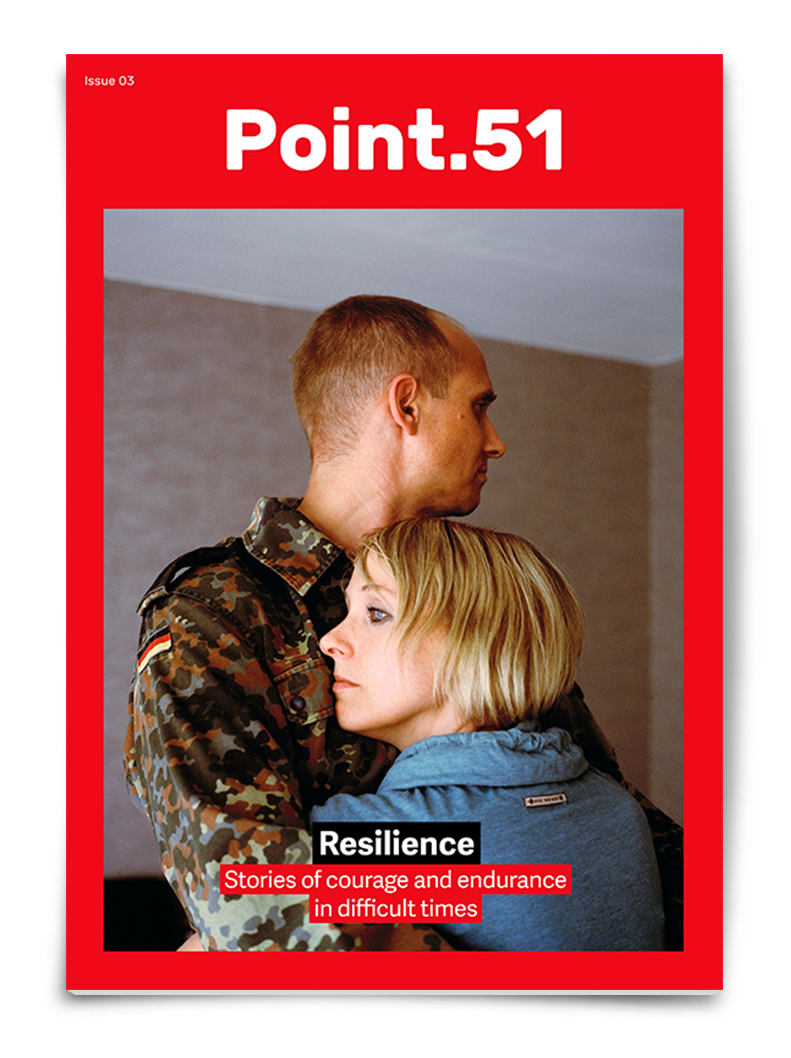

This story is from Point.51 03: Resilience.

You can order the magazine from our shop and have it delivered straight to your door.

As the UK goes through the process of leaving the EU, Albania’s quest for membership has prompted some fundamental questions about what it means to be "European".

Photographer John Angerson travels to the precise locations of some of the most important events in Britain’s recent history, showing these locations as they are today.

In the mountains of northern Albania, the “shepherds life” is little-known – and a long way from the romanticised ideal.

German veterans of Kosovo and Afghanistan who have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder often feel isolated from a society where the experience of war is considered a “taboo” subject.

.jpg)