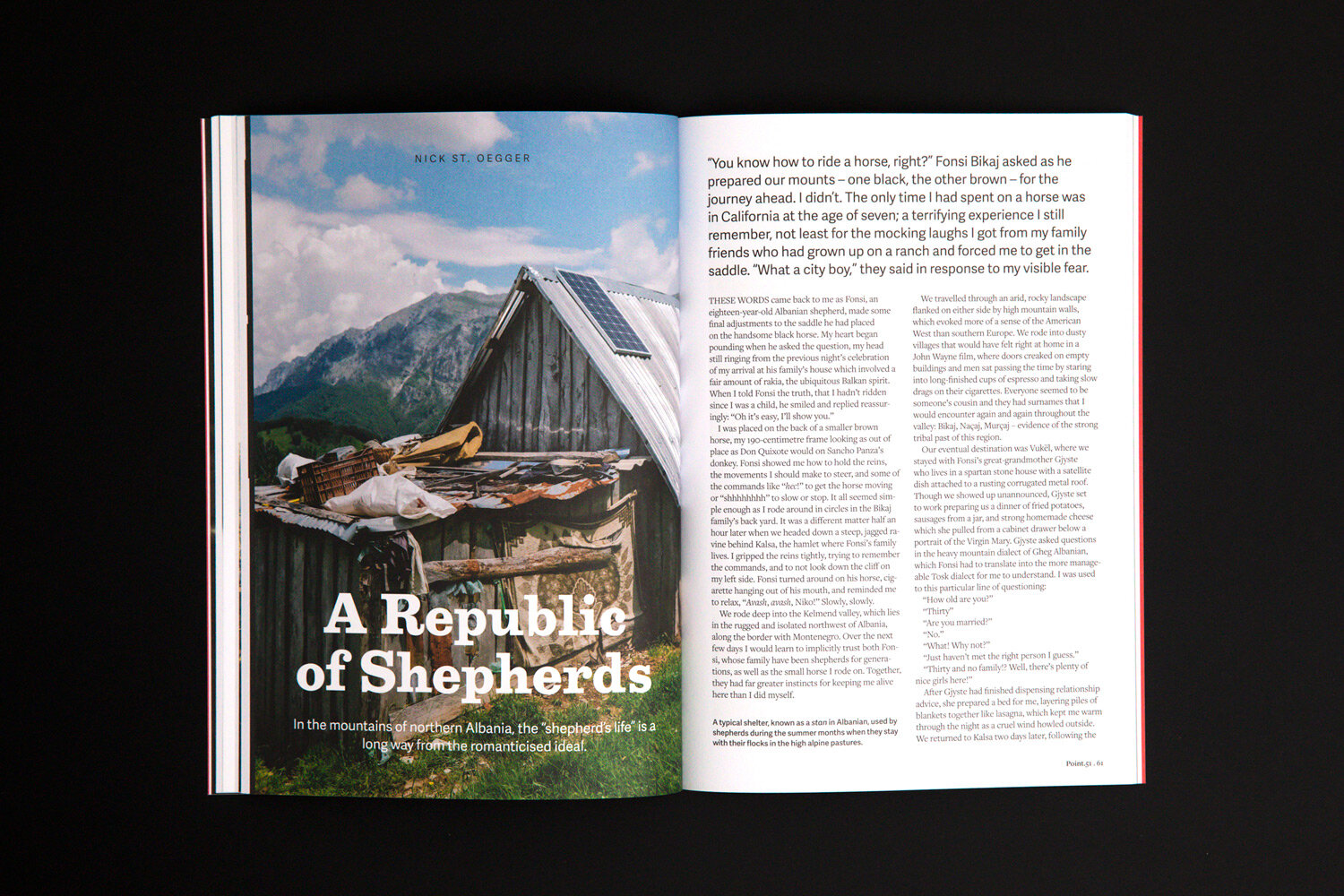

A Republic of Shepherds

In the mountains of northern Albania, the “shepherd’s life” is a long way from the romanticised ideal.

“You know how to ride a horse, right?” Fonsi Bikaj asked as he prepared our mounts – one black, the other brown – for the journey ahead. I didn’t. The only time I had spent on a horse was in California at the age of seven; a terrifying experience I still remember, not least for the mocking laughs I got from my family friends who had grown up on a ranch and forced me to get in the saddle. “What a city boy,” they said in response to my visible fear.

These words came back to me as Fonsi, an eighteen-year-old Albanian shepherd, made some final adjustments to the saddle he had placed on the handsome black horse. My heart began pounding when he asked the question, my head still ringing from the previous night’s celebration of my arrival at his family’s house which involved a fair amount of rakia, the ubiquitous Balkan spirit. When I told Fonsi the truth, that I hadn’t ridden since I was a child, he smiled and replied reassuringly: “Oh it’s easy, I’ll show you.”

Lunch at the Bikaj family’s stan. Sheep’s milk is used to produce yoghurt and cheese, and the top and bottom layers are skimmed and baked into other dishes. Photographs: Nick St. Oegger

I was placed on the back of a smaller brown horse, my 190-centimetre frame looking as out of place as Don Quixote would on Sancho Panza’s donkey. Fonsi showed me how to hold the reins, the movements I should make to steer, and some of the commands like “hec!” to get the horse moving or “shhhhhhhh” to slow or stop. It all seemed simple enough as I rode around in circles in the Bikaj family’s back yard. It was a different matter half an hour later when we headed down a steep, jagged ravine behind Kalsa, the hamlet where Fonsi’s family lives. I gripped the reins tightly, trying to remember the commands, and to not look down the cliff on my left side. Fonsi turned around on his horse, cigarette hanging out of his mouth, and reminded me to relax, “Avash, avash, Niko!” Slowly, slowly.

We rode deep into the Kelmend valley, which lies in the rugged and isolated northwest of Albania, along the border with Montenegro. Over the next few days I would learn to implicitly trust both Fonsi, whose family have been shepherds for generations, as well as the small horse I rode on. Together, they had far greater instincts for keeping me alive here than I did myself.

Fonsi Bikaj moves a herd of sheep from near the family’s winter home to the shelter where they stay during the summer months for the sheep to graze in high mountain pastures. Earlier in the day, his father Gazmend had taken the sheep from their owner in the lowlands outside the city of Shkodër and walked with them into the Kelmend Valley – a distance of 65km. This process of transhumance has been practiced in the mountains for hundreds of years and risks dying out as the population decreases along with environmental threats being posed by hydropower development on rivers in the area. Photo: Nick St. Oegger

We travelled through an arid, rocky landscape flanked on either side by high mountain walls, which evoked more of a sense of the American West than southern Europe. We rode into dusty villages that would have felt right at home in a John Wayne film, where doors creaked on empty buildings and men sat passing the time by staring into long-finished cups of espresso and taking slow drags on their cigarettes. Everyone seemed to be someone’s cousin and they had surnames that I would encounter again and again throughout the valley: Bikaj, Naçaj, Murçaj – evidence of the strong tribal past of this region.

Our eventual destination was Vukël, where we stayed with Fonsi’s great-grandmother Gjyste who lives in a spartan stone house with a satellite dish attached to a rusting corrugated metal roof. Though we showed up unannounced, Gjyste set to work preparing us a dinner of fried potatoes, sausages from a jar, and strong homemade cheese which she pulled from a cabinet drawer below a portrait of the Virgin Mary. Gjyste asked questions in the heavy mountain dialect of Gheg Albanian, which Fonsi had to translate into the more manageable Tosk dialect for me to understand. I was used to this particular line of questioning:

“How old are you?”

“Thirty”

“Are you married?”

“No.”

“What! Why not?”

“Just haven’t met the right person I guess.”

“Thirty and no family!? Well, there’s plenty of nice girls here!”

After Gjyste had finished dispensing relationship advice, she prepared a bed for me, layering piles of blankets together like lasagna, which kept me warm through the night as a cruel wind howled outside. We returned to Kalsa two days later, following the course of the Cemi river, where plans to build hydropower dams have set the whole valley on edge. People are worried about the effects the dams will have on their water supply, and on the environment as a whole. It doesn’t take much to upset the natural balance in a remote place like Kelmend.

During a break to let the horses drink from the river, Fonsi received some bad news on a mobile call. One of his friends, Sebastian, had been killed that morning: electrocuted by a live wire while working at a hydropower plant in a nearby village. Many of the locals told me that young men from the area were being employed to work at the hydropower station or to help with new construction, often in hazardous conditions. Due to the poverty and lack of other employment opportunities in the area, many are willing to accept these risks. Fonsi seemed unfazed by the news. “These things happen here, Niko.”

• • •

The reality of Sebastian’s death didn’t set in until we had returned to Kalsa, where the whole Bikaj family had gathered in the sitting room. Gazmend, the head of the family, spoke on the phone with Sebastian’s father, a teacher at the hamlet’s sole primary school. Though everyone already knew Sebastian’s fate, there was a sense that it didn’t become real until his father spoke the words. The outpouring of grief was strong and immediate, not just in the Bikaj household, but all around.

In less than an hour, I was making the trek with the Bikaj men down to the main town of Tamarë where they would pay their respects to Sebastian’s family and I would get on a bus back to the city of Shkodër, where I lived. We started as a group of five, mostly silent, until we came to a house along the way where one of the men would yell out and another would emerge to join us; our black clad group slowly growing like the shadows engulfing the valley around us. It was then that I understood that this wasn’t just a loss on a personal level for Sebastian’s family, or the individuals who knew him: it was a loss for the entire community, felt in every house and every heart. Connections run

deep in Kelmend.

That was my introduction to the Malësorët, the highland peoples who inhabit Albania’s northern mountains. Dispersed between the Kelmend and Dukagjin regions, the Malësorët historically lived in a tribal system cut off from and independent of the Ottoman and Montenegrin powers who vied for control of the region over the last 500 years. The largely Catholic population of Kelmend also put up fierce resistance to the communist regime established by Enver Hoxha after WWII, and were heavily persecuted as a result.

After Hoxha’s death in 1985, power started to slip from the communists until they were eventually voted out of power amid widespread civil and economic unrest in March 1992. Mobility became possible for a population that had been tightly controlled, and large numbers of Malësorët moved down to the lowlands around the city of Shkodër or moved abroad and never looked back. Today, the Malësorët aren’t quite the brave, armed warriors they have been over the last few centuries, but many who remain in the mountains carry on a traditional way of life that has existed for centuries in Europe but has been slowly disappearing: pastoralism.

Usually practiced in dry climates where vegetation becomes scarce in summer, pastoralism involves shepherds travelling with their animals during different times of the year to find greener pastures. In some places, pastoralists live a perpetually nomadic life – like the Sámi people of northern Scandinavia – while in the north of Albania and elsewhere, shepherds relocate to high alpine regions during the summer months and return to their permanent homes in the lowlands before winter, a process called transhumance.

• • •

Before I spent time with the Malësorët, my conception of pastoralism had mostly come from romanticised descriptions in classical poetry and literature, or the wildly exaggerated, stereotype-laden stories I had heard from people in the lowlands of Albania. The use of pastoralism in literature has existed for thousands of years, dating back as far as the poetry of the Roman poet Virgil, through to more modern writers like John Milton and William Wordsworth. Shepherds in this genre of literature are usually presented as pure, existing in idyllic rural landscapes or utopian societies free from the anxieties and corruption of the city.

Gazmend Bikaj rests after a day herding sheep in the high pastures above Lepushë, deep in the Kelmend Valley of northern Albania. Photo: Nick St. Oegger

Virgil presented the shepherds as country poets, using their innocent nature to veil his own criticism of public figures or events of the day. In later 18th and 19th century literature, there was the archetype of the noble savage: that “uncivilised” man living simply and in touch with nature, uncorrupted by the influences of the modern industrialised world. Wordsworth, the English romantic poet, described the shepherds of the Lake District as existing in an idyllic kingdom bound by the mountains: “Towards the head of these Dales was found a perfect Republic of Shepherds and Agriculturists … the members of which existed in the midst of a powerful empire, like an ideal society or an organised community whose constitution had been imposed and regulated by the mountains which protected it.”

This version of pastoral living conjures up a simple life spent moving through beautiful countryside with an obedient flock, eating healthy food and reclining in the shade of large trees to sleep through the afternoon heat, without a care about the state of the rest of the world or what politicians were saying in the cities. But at the other end of the spectrum there are some fairly negative modern stereotypes.

During my first journey to Albania, the owner of a hostel I stayed at tried to “warn” a group of Belgian hikers who were intent on heading into the Albanian Alps. He described the Malësorët as dangerous, bandit like people who roamed the mountains clutching Kalashnikov assault rifles – especially in the Dukagjin region where they supposedly guarded large stockpiles of illicit drugs. A lot of these rumours were rooted in the period of civil unrest that gripped Albania in 1997 when the government collapsed, military bases were raided, and bandits did indeed roam the mountains.

When I lived in the northern city of Shkodër, I also heard things in passing about the Malësorët who had moved down to the city and were concentrated in the Rus Maxharr neighbourhood closest to the mountains. People joked that they were backwards, illiterate, that they had sex with their sheep, or that they “live like they’re in the Middle Ages”. There was a clear and prejudiced divide between the well-dressed, “cultured” people of the city and the craggy, weathered people of the mountains who were typically taller, with lighter-coloured eyes, and spoke in a different dialect. There was also plenty of talk about “blood feuds”, the centuries-old practice of vendetta that existed in the mountains and sometimes spilled over into Shkodër when warring families moved to the city.

These two conflicting stereotypes of the shepherds echoed in my head when I agreed to join Fonsi Bikaj and his father Gazmend as they made the journey to the high pastures at the start of the summer of 2019. After a two hour ride in a battered Mercedes bus, I found Gazmend and Fonsi in Tamarë, the administrative centre of Kelmend. The minibus deposited me into a sea of 220 sheep, anxiously standing in the middle of a two-lane road. Gazmend greeted me with a beaming sunburned face, kissing me four times on both cheeks in a show of affection that is customary between good male friends in Albania. It was late in the afternoon and he had been walking since 5.00 am with the sheep, so he explained that it would be up to Fonsi and I to walk them the remaining forty kilometres to their summer shelter in the alpine pastures.

Gazmend finished a large glass of cold beer, gave me a wink, and jumped into a waiting Mitsubishi Pajero 4x4 with some other men, speeding off on the road that we would be walking down. Even in the late afternoon, the intensity of the Mediterranean sun was overbearing, beating down directly from above, and radiating a scorching heat off the tarmac below us as we set out. It didn’t take long to realise it had been a prudent decision to bring my headlamp, as I saw the sun would soon disappear behind the high mountains. After forty-five minutes of walking, we could still see Tamarë and had only covered about two kilometres. Any illusions I had about sheep being obedient and organised were quickly dashed.

• • •

The sheep went everywhere except in a straight line, diving off the road towards any source of water or hint of greenery that could be eaten. When a car, or truck, or group of tourists on motorbikes came across us, the sheep couldn’t have cared less. Horns blared loudly and drivers yelled as we frantically beat a path for them to get through. This happened over and over again as we moved higher through the mountains, albeit at a snail’s pace. I stopped taking photos, and my concentration completely shifted to chasing down the two or three smug sheep who had run up a hill. Leaving them behind was not an option.

We started to lose light fast, so I turned on my headlamp, the only thing to give motorists advance warning that they were about to plow into us. This wasn’t the life I had been promised by the poets. We finally arrived at the Bikajs’ wooden hut at 3.00 am, a full moon guiding us along the final stretch through a forest. Inside, there was an exposed dirt floor, but I was surprised to find many of the comforts of home: couches, beds, a roaring stove, and beautifully organised shelves with supplies. I was falling asleep on my feet, but Gazmend’s wife Lula had prepared us a meal. We devoured it in silence, knocking back homemade bread and salty cheese with shots of rakia, before falling into a deep, dreamless sleep.

Lula Bikaj speaks on the phone with a family member as she watches over a flock of sheep. Shepherdesses take on the dual roles of caring for the flock, taking them deep into the rugged mountains so they can graze, as well as maintaining the household and caring for their own families. Photos: Nick St. Oegger

I awoke the next morning to a symphony of crickets and the distant sound of someone chopping wood. Stumbling outside, my eyes struggled to comprehend the scene in front of me. In the lowlands, and around Shkodër where I was living, most of the vegetation had already been scorched by the intense Mediterranean sun, transformed into shades of yellow and brown. Gazing around at the lush fields and forests around me, I understood what all the struggle the previous day had been for.

Gazmend was hunched awkwardly against a fence, trying to make a call with an antenna he had rigged up to boost the signal of his ancient Nokia mobile phone. I was relieved to be somewhere without mobile reception, without notifications, emails or news updates. For the shepherds though, their mobile phones are a vital tool for checking in with each other and calling home to arrange supplies or transport. I turned to head back inside for breakfast, noticing a trio of small solar panels on the corrugated metal roof of the structure. Even here, some of the conveniences of the modern world trickle in.

Back inside, I found Lula looking skeptically at the jar of pesto I had brought: “Niko, what is this?” I told her it was a sauce for pasta. She opened the jar, put her nose close to take a sniff of it, wrinkled her face in displeasure, and then quickly put it back on the shelf. “Maybe another time,” she said politely. When I visited a few months later, the pesto was in the same place she’d left it.

We drank more coffee and rakia, and then the day’s activities began. Gazmend put the finishing touches on a part of the fencing that needed repair, while Lula gathered the sheep to be milked. This would become a familiar daily rhythm during my time with the Bikaj family. Every morning and evening the sheep were corralled into a separate pen in their enclosure where Lula and one or two of her daughters waited at an exit point. Every sheep had to be milked one by one, a process taking several hours. Then they were led out to graze, often far from the encampment into the surrounding mountains. Someone would yell from what seemed like miles away that lunch was ready, we would head back with the sheep, eat, take a nap, and then the process would start again.

At the start of the summer, there was a light, carefree feel to what was ultimately hard and physically demanding work. That was still the case when I headed back to Shkodër after a week with the Bikaj family. But when I returned later in the season, the longer-term reality of this life was more clear. I found the Bikaj’s tired and sunburned with cuts and bruises on their hands, and the sheep mostly laid out in their pen, exhausted as well. The family’s hut, which had been so organised and tidy before, now looked disheveled. Parts of the roof were broken from a storm and it was full of insects. Two months of heat and back breaking work in the wilderness had started to take a toll.

Gazmend and Lula Bikaj play with their youngest son, Valdijan. The family have seven children ranging from one to ninenteen years of age, all of whom have a role to play during the transhumance period in the summer months.

The Malësorët shepherds and their pastoral life are mostly absent from material promoting tourism in Albania’s northern mountains. The tourism sector has been steadily growing in recent years as the country continues to shrug off some of the more negative and persistent stereotypes that have followed it, choosing to market its untouched mountains and coastline to intrepid adventure lovers. The official tourism board website mentions the “crystal-clear waters of the Cemi River, creating a beautiful contrast with the surrounding landscape”, and that visitors can expect to enjoy themselves “trekking, mountain climbing, skiing, or fishing for mountain trout”.

More visitors are indeed coming to the so called “Albanian Alps”, especially the neighbouring Theth and Valbona National Parks, bringing important revenue for some in the local communities. But there are also the initial, and somewhat inevitable, signs of larger scale tourism in the construction of new guest houses, group tours with non-local guides, and increasing levels of waste on trails and in lakes. Such places are often seen and treated differently by outsiders compared to those who have lived there for centuries.

James Rebanks, a shepherd in northern England’s Lake District, touches on this in his book, The Shepherd’s Life. Inhabited for centuries by farmers and shepherds, the Lake District only became a holiday destination towards the end of the 18th century. As a boy, Rebanks had been completely unaware of the romanticised outsider view of the lands his family worked on until a teacher presented his class with the poetry of Wordsworth. “I realised then with some shock that the landscape I loved … the place known as ‘the Lake District’ had an ownership claim submitted by outsiders and based on principles I barely understood.”

With the spread of romanticism and the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, such places increasingly became an “escape” for well-heeled urban dwellers, where they found beauty and emotional value in features of the landscape that the shepherds viewed in purely practical terms.

This continued into the 20th and 21st centuries, with outsiders now buying properties that their original owners could no longer afford, sometimes creating “culture clash” in communities they didn’t understand. “Some new neighbours called the police because they could hear men shouting on the fells above with dogs,” Rebanks writes. “We were simply gathering our sheep. Two worlds that didn’t understand each other were colliding.”

• • •

I returned to Kelmend at the start of autumn to join Gazmend and his family as they went back one last time to work at their summer encampment. We met early in the morning in Tamarë and piled into two old Mercedes sedans followed by a blue lorry. Driving on the winding road that Fonsi and I had led the sheep down three months previously, we passed an area where construction had started on a dam. Our driver shook his head and made a disapproving clicking noise with his tongue. Since I had last been in the area, locals had caught wind of plans to build three new dams in the next valley over. Change, it seemed, was coming quickly.

Around one of the bends in the road, when we had reached a certain elevation, the landscape changed dramatically. The trees in the lowlands still had the muted, scorched brown tones of summer, but in the highlands they had exploded into a full and vibrant range of autumnal reds, yellows, and oranges. Albana, one of Gazmend’s older daughters seated next to me, gasped with wonder at the sight. “Ahhh, how beautiful is the bjeshk?!” she exclaimed, using the Albanian name for the high mountain areas.

When the paved road ended, we got into the back of the blue lorry, which took us the final ten kilometres to the encampment. As the lorry rumbled down the heavily rutted forest road, Gazmend, his daughters, and I tried to keep ourselves stable in the back as tools and beer cans started flying around. One of the cans burst and Gazmend playfully picked it up, spraying it towards Albana and I.

We suddenly arrived at the encampment, the motor cut out and I was immediately taken by the silence. Gone were the sounds of the summer, the crickets, the birds, the sheep, and the distant yelling of other shepherds. We stood in the field for several moments taking in the stillness and the colours around us, before a Bluetooth speaker someone had brought along started belting out Albanian folk music. We unloaded the tools, and the task at hand quickly became clear.

The family had already taken most of their supplies back to their permanent home for the winter, and had harvested the vegetables from what had been a lush garden filled with carrots, onions, and cabbage. Behind that garden was a large field of potatoes, and they needed to be tilled. Rubber boots were donned, cigarettes lit, and an already tired-looking horse was fitted with a plough and taken to the field.

Gazmend led the horse in sweeping passes, as giant potatoes burst out from the soil. Fonsi, his sisters, and their uncle scrambled to catch the potatoes that went tumbling, trying to organise them into larger piles while Gazmend turned the horse around and started the process again. After the whole field was tilled, every single spud was gathered up and put into canvas sacks – easily weighing thirty kilos – and loaded into the back of the lorry.

It was hard work, under a cloudless autumn sky with a sun that hadn’t lost any of its potency from the summer months. Yet the whole experience had an air of celebration, like a farewell party for a dear friend. Everyone danced and sang along to the folk music, guzzling energy drinks that claimed to have “original American taste”, while Gazmend pushed the horse down the field holding the top of a beer can between his teeth. In the evening, after the last sack of potatoes had been hauled into the lorry, we ate the last of the food leftover from the summer, while the women danced long into the night, lit by a full moon rising over the distant mountain peaks.

I parted ways with the Bikaj family the next day as they headed back to their home near Tamarë, and I went on to spend a few days hiking in the surrounding area. In front of a roadside café we took turns kissing cheeks, shaking hands, and promised to keep in touch until the next time I saw them. Gazmend and the girls jumped into the waiting Mercedes sedans and followed the blue lorry, whose suspension was sagging from the weight of the potatoes. Fonsi and I finished a coffee, smoked one last cigarette together, and then I watched him mount his horse and disappear into the horizon.

The next day, as I climbed towards a peak on the border with Montenegro, I lost track of the trail I had been following and became frustrated at not being able to reach the top. I felt lonely without the shepherds, and as I sat taking a break, I thought about how different my experience of the mountains had been during my time with them. I hadn’t thought about what peaks I needed to climb, how many emails I was missing, or if I should be generating more user engagement with my Instagram feed. I felt more connected to the land, and to myself.

I thought about being back down in the city of Shkodër, where people would be parading down the boulevard in their best clothes or glued to their phones at cafés, only looking up at the sound of a fast car full of young men trying to catch the attention of some girls. In the mountains, nobody was trying to impress anybody, to look a certain way, or to compete for followers or affection. The pastoral life may not always be like the one described by Wordsworth, but nor is it just back-breaking work without appreciation of the landscape and acknowledgement of the special position that shepherds hold within it.

This story is from Point.51 03: Resilience.

You can order the magazine from our shop and have it delivered straight to your door.

As the UK goes through the process of leaving the EU, Albania’s quest for membership has prompted some fundamental questions about what it means to be "European".

Rafael Bastido de los Santos has a master’s degree and speaks excellent English, but he couldn’t find one stable job – so he worked three part-time. Like many young Spaniards, he faces a choice between life at home and more attractive career opportunities abroad.

There are 800,000 informal and unpaid caregivers in Portugal, but their work is largely hidden and their stories untold. Photographer Teresa Nunes’ mother is one of them.

Emma Ringqvist sailed the Atlantic Ocean alone for nine months, including sixty-seven days where she was completely out of reach of both land and people. It was the purest experience of loneliness.