Behind the Story: Hugh Quigley

How do you become a serious documentary photographer, in an era of click-bait journalism, social media saturation, and declining opportunities?

Three years ago, Hugh Quigley was a “nobody”. That is, he was virtually unknown in the documentary photography world – even in his native Ireland.

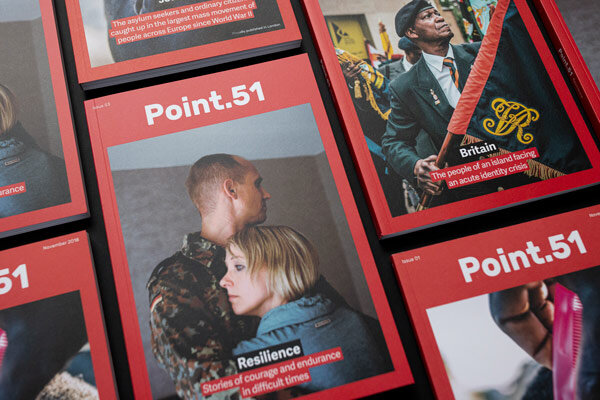

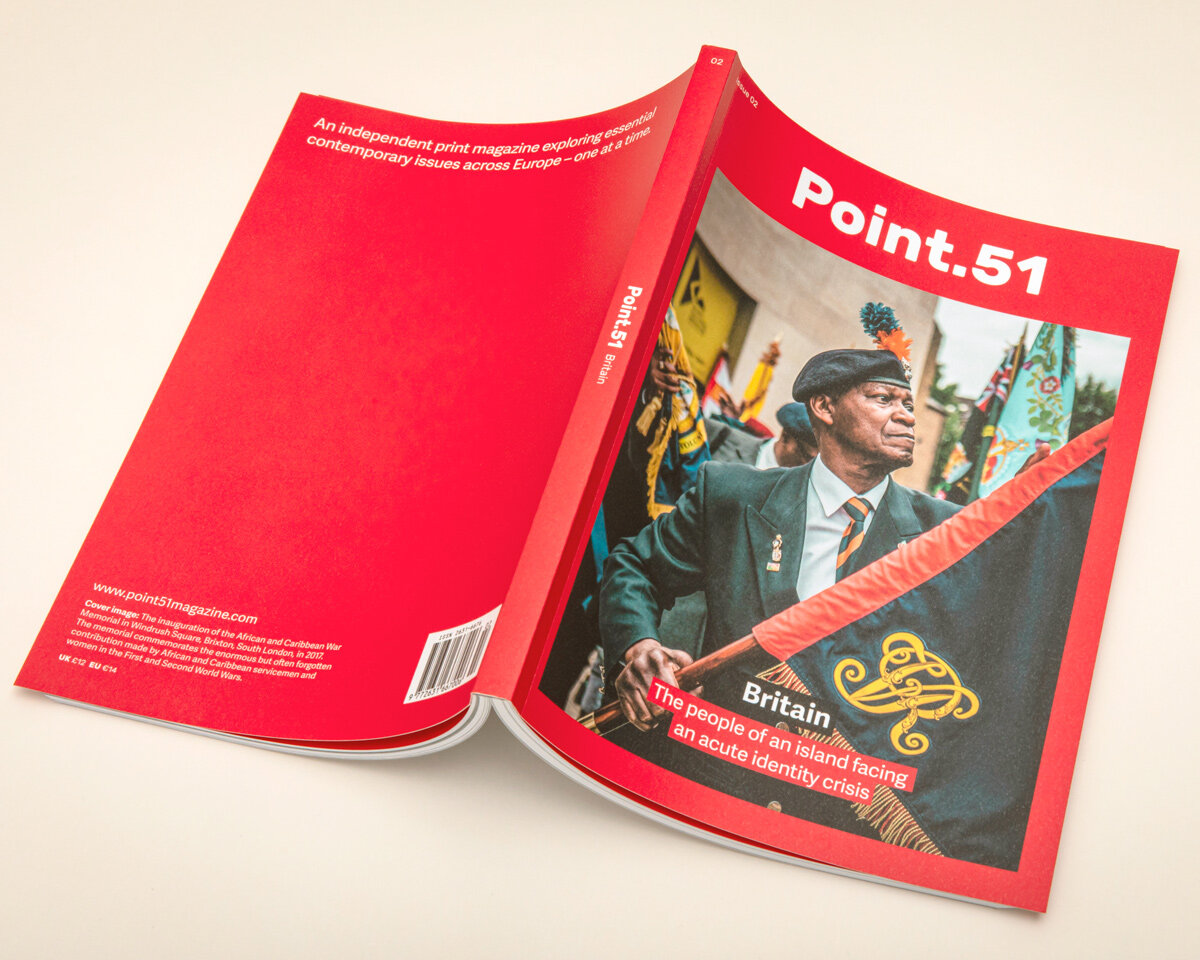

Today, Hugh has achieved some impressive feats. His work, which explores the relationship between humans, animals, and nature, has been critically recognised as part of Source magazine's graduate photography competition. He's also shot four significant feature stories for print publication (including two for Point.51).

Finally, he was the photographer's assistant for Linda Brownlee, who recently shot some iconic medium-format images of Sally Rooney for the Guardian (the one with the owl, that everyone has been talking about).

In our Q&A (lightly edited for length and clarity) Hugh gives us some more details about his career to date, and what he’s been up to recently...

Q: You grew up in rural Ireland – in County Tipperary – how did your upbringing influence the sort of photographer you wanted to be?

Growing up in my part of rural Ireland was a mix of spending lots of time walking in the mountains and woods, jumping into the river Suir, drinking in fields, and having not much else to do beyond that. The older I got while living in Tipperary the more I wanted to get out of it. Ireland still has a huge culture of emigration for young people (mostly to Canada, Australia, and the UK) due to its incredibly restrictive house and rental prices and the limited opportunities for graduates. Both of my siblings moved away and a lot of my friends have lived abroad for at least a few years. After living in Dublin for six years though, I get more and more excited to see the mountains around my hometown on the drive down; the Galtees, the Comeraghs, the Knockmealdowns, and Sliabh na mBan.

I think growing up in the country as someone who doesn’t care about sports, it only makes sense that I’d take such a strong interest in nature and wildlife. But being surrounded by intensive farming and monoculture spruce forestry, while constantly being taught about mankind’s impact on the earth, made me start to question what I was seeing.

I eventually started to become more interested in the grey areas of our interactions with the natural world, where it’s not as clear as “this is bad but this is good,” and the implications of considering humans as much a product of nature as anything else. Having been interested in photography since about the age of nine or ten, this curiosity grew with my understanding of what could be achieved with a camera, and it became a great way for me to process what I was seeing. I think I felt an urge to record my slice of what I think is a pivotal era in human history.

Q: We first met you in 2019, during the Dublin launch for the first issue of Point.51, when you were still a student. Did you have any idea, at that stage, where you would end up as a photographer? Take us through what’s happened since then, in terms of how you’ve “broken in” to the industry?

I didn’t, really. I knew that my practise was going to be documentary-focused and I knew the general theme of the things I wanted to cover, but I was completely lost when it came to the matter of making a living from it – which I’ve since realised is all but impossible nowadays, at least in Ireland. Soon after graduating, I decided to quit my job in a furniture hire warehouse and try to get work as a freelance photography assistant working on commercial shoots. Two weeks later, Ireland’s first lockdown came into effect and the apocalypse sort of happened for a while, so not much changed for a few months.

What the lockdown gave me time to do, though, was get things in place for when I’d have the freedom to start doing projects again. I also spent a few weeks ringing as many commercial photographers in Dublin as I could to let them know that I’d be available to assist as soon as things started picking up again, which they eventually did.

Since then, I’ve been trying to strike a balance between earning enough to live in Dublin (bizarrely, the fourth most expensive city to live in Europe after Zurich, London and Lausanne) and having enough time to work on as many long-term documentary projects as I can. I’ve been very lucky to have met some really helpful editors [at Point.51 and the Dublin Inquirer], who seem to like my work, and photographers who are willing to give advice.

Q: It seems like your first “success” came with the praise you received through the Source magazine graduate competition. Tell us about your photo book Laws of the Leash – how it got started, what you learned, how that experience influenced your later work?

Laws of the Leash started as an assignment in the third year of college. I decided to document the national coursing finals that happen every year in Clonmel, my hometown. Coursing is a sport that involves two greyhounds chasing a captured wild hare across an open field track for 400m. The winner is the dog that is the first to get close enough to the hare to make it turn from a straight line. Ireland is one of only a handful of countries left that haven’t outlawed coursing and, even though I grew up with it on my doorstep, I still didn’t really know anything about it.

I managed to get access through a family friend who’s a sports photographer. After meeting the vice-president of the Irish Coursing Association, I showed up to the three-day event and shot about 25 rolls of medium-format film. The project expanded until I had spent eighteen months following the processes involved in capturing wild hares, breeding the greyhounds, looking after the hares once they’ve been captured, and getting to see how much the sport means to the people involved.

I was lucky to have met with very helpful participants, although some were understandably wary of me. I was struck by people’s willingness to open up their lives to me. Coursing is always surrounded by controversy and opposition from animal rights groups, and I fully understand why and agree that it is inherently cruel, but I found that the reasons for people’s involvement in the sport extend to matters of cultural identity, family heritage spanning hundreds of years, and a sense of community for rural people who have diminishing opportunities to be social.

It was full of interesting contradictions and difficult questions. That was one of my favourite parts of the project: trying to show something complicated and emotional in a balanced and neutral way.

Q: You often work in film – in medium-format – rather than digital. Why?

I fell in love with medium format film when I rented one of my college’s Hasselblad cameras. Soon after, I managed to get a really good deal on one of my own and have been absolutely hooked since. I didn’t touch my digital for over a year after getting it.

I love how the limitations of working on a completely manual system with only twelve shots per roll and a very delicate depth of field force me to slow down and make sure that I’m doing everything right and making the most of each exposure. It works out at costing over a euro per shot after processing and God knows how much time goes into scanning, dust-removal and colour work. There’s a real flippancy with digital that, although really useful in certain situations, usually leads to me taking worse photos.

Blasting through a hundred photos in the hopes that there’ll be a usable one in there somewhere is engaging a lot less of my creativity and intuition. And film just looks better, especially medium format! The depth of colour, tonal range, and detail is really amazing and gets my heart pumping in a way that digital just doesn’t. I love square format too, in spite of the issues it can create in layout design. Something about it feels really tidy and contained.

Q: For Point.51 04: Nations, you shot the images for a 10,000 word profile of Ellie Berry, a young woman adventurer and long-distance hiker who grew up near you, in rural Tipperary. What was it like to return to familiar territory for your first major feature story?

I really enjoyed the trip back home for that part of the story. I’ve spent loads of time in that area of the mountains and knew that it would be a nice shoot.

It was a bit peculiar walking around the area with a brief in mind, though – it made me think about what people unfamiliar with Ireland and the area might think of it. Most of Ireland was hit very hard by the global recession of 2008 and still hasn’t recovered.

A lot of the buildings in the local villages and towns are empty and decaying, so it wasn’t easy to see with an outside audience in mind, especially considering how beautiful an area it’s in and how bustling I remember it being as a child. In the end, the photos of this side of the village didn’t make the final edit, but it was an interesting experience.

Q: You recently assisted Linda Brownlee, an established medium format photographer, in capturing Sally Rooney for a Guardian profile. You also shot some images for Meg Bernhard’s profile of Lucy Sweeney-Byrne, another “Irish Millennial Writer” (Point.51 03). Was it a surprise to you that you’ve picked up this kind of work in Ireland, rather than, say, moving to New York or Berlin or London and trying to “break through” there?

Getting to work with Linda was a great experience, it was the first shoot I’d assisted on that used medium format so I spent the whole day loading film into two different cameras, including while on a rowboat in a river – that was a challenge. I got that job because I was the only available assistant who had experience with medium format and could drive. It’s true that the majority of the shoots I work on are commercial advert shoots, but I have had some great experiences on music shoots and some of the more creative ad shoots. These kind of shoots would be a lot more common in the places you mentioned though, Ireland doesn’t have a huge amount of international celebrities. But there are always a few!

I’d really recommend assisting to anyone who wants to get into any aspect of the photography industry. On top of often being a really interesting and fun job, it’s a fantastic way to learn invaluable information that’s difficult to find any other way. You’re also developing professional relationships. It’s basically a requirement to own a car if you want to make a living with it though.

Q: You’ve just completed a significant photo essay for the Dublin Inquirer (a “slow journalism” newspaper), and you’re now at work on a long-term project about biodiversity and re-wilding in rural Ireland. Tell us about both of these experiences, and what you’ve learned from these?

The photo essay for the Dublin Inquirer is about a Men’s Shed reopening after lockdown. Men’s Sheds are community projects where usually retired men can do woodwork projects, go on day trips, or just get together for tea and lunches. I spent about two months getting to know them, photographing their activities, and speaking to them about the importance of the group.

It was a really enjoyable, positive story to work on, but it did remind me of the importance of allowing adequate time for a project. There was a fair bit of waiting for things to happen, and hoping that I was able to attend [their events] around my other work. The extra time did allow me to build more of a relationship with the group though, which can only make the work better.

The project on rewilding is something I’ve been wanting to do for a long time and am really excited about. Ireland’s first dedicated wildlife hospital opened in March and is about half an hour’s drive from where I live. They’ve been really open and helpful and I’ve gotten to hang around some amazing animals that I’ve never been able to see up close in the wild: otters, badgers, pine martens -- a baby crow even landed on my shoulder!

From here we’ll be looking at rewilding in a broader sense and I’m really excited to get into it. But again, it’s going to take a lot of time.

One thing I was taught about recently was the so-called "Triangle of Death". It refers to a project only ever being able to be two of the following: good, quick, or cheap. I’m hoping that it’ll be good and the travel costs are manageable, so I’m okay with taking my time on this one.

Q: What would be your advice to people like you – who grew up on the periphery, without easy access to contacts and mentoring – in terms of creating a pathway to becoming a working documentary photographer?

If possible, get into assisting photographers whose work you admire. There’s always something to learn on a shoot if you’re looking for it, especially starting out.

Nobody that I’ve met is able to make a living from just being a documentary photographer in Ireland, so loads of the documentary photographers you like are probably doing commercial work that they need assistants for as well. Once you’ve built up a good body of work you can start applying for grants and residencies too. This isn’t something I’ve gotten into yet, but I know people who have been able to basically get paid (sometimes very well) to live abroad for a few weeks or months and make a project, or even just to research or use facilities.

I’m still very much trying to break into the industry and have a lot left to learn, but none of the progress that I’ve made or luck that I’ve had would have happened if I hadn’t tried my best to make a good project in the first place. Once you have a good project, start contacting photographers and editors, asking for advice and figuring out how the system works.

Also, take your work seriously. I noticed a big increase in the amount of time that I spent on researching and organising projects when I started to refer to sitting at home reading on my laptop all day as “working”. People want to see dedication, and it’s easy to spot when people don’t give a shit about their work. And just be nice!

See more of Hugh’s work:

This is Just How it Happened (Point.51) • Tough Soles (Point.51) • The Cabra Men’s Shed (Dublin InQuirer)