Secretive “closed towns” have existed in Russia since the mid-1940s, when the Soviet Union began to develop its Cold War-era nuclear arsenal in competition with the United States, and later, Britain and France. Positioned in locations across the country, these towns were built to house sensitive military, research, and industrial facilities; along with the workers, engineers and scientists that were needed to run them. Residence was by invitation only, and the towns did not appear on Soviet maps.

Each town was known only by a generic number, a pochtovy yashchik or “mailbox” to which correspondence could be sent, removing the need for an address that might identify their location. Closed towns were designed in a particular way, each following a similar layout. They were often referred to as “clones” because of their similarity to one another. Authorisation was required to enter or leave and many residents spent their entire lives within the confines of the walls that separated them from their surroundings.

But far from a barrier keeping them from the world outside, those living within were often grateful for this exclusion: for the security it brought, and for the privileges it granted by allowing only a select few to pass. Once inside, residents enjoyed access to a range of luxury amenities: theatre, sports facilities and ski slopes; better schools, healthcare, food, goods, and housing. It was hoped that by providing everything their residents might want and need, they would have no desire to leave. “The state created a world of its own,” explained Oxana, who works at the local archives. For residents, the knowledge of their privileged position – set apart from the difficulties and deprivation that many Soviet citizens faced elsewhere – also made for a powerful incentive to stay. But for those living beyond their walls, closed towns were no more than an imagined utopia: the kind of place people dreamed of living in, but never knew existed.

“Before we moved here, I had friends ... We had a group of three families, we were together at the weekends and on holidays. But then, I moved to a new place and no one saw each other as frequently. We had our own lives. We didn’t have common interests anymore. Perhaps this way of thinking comes from this environment.”

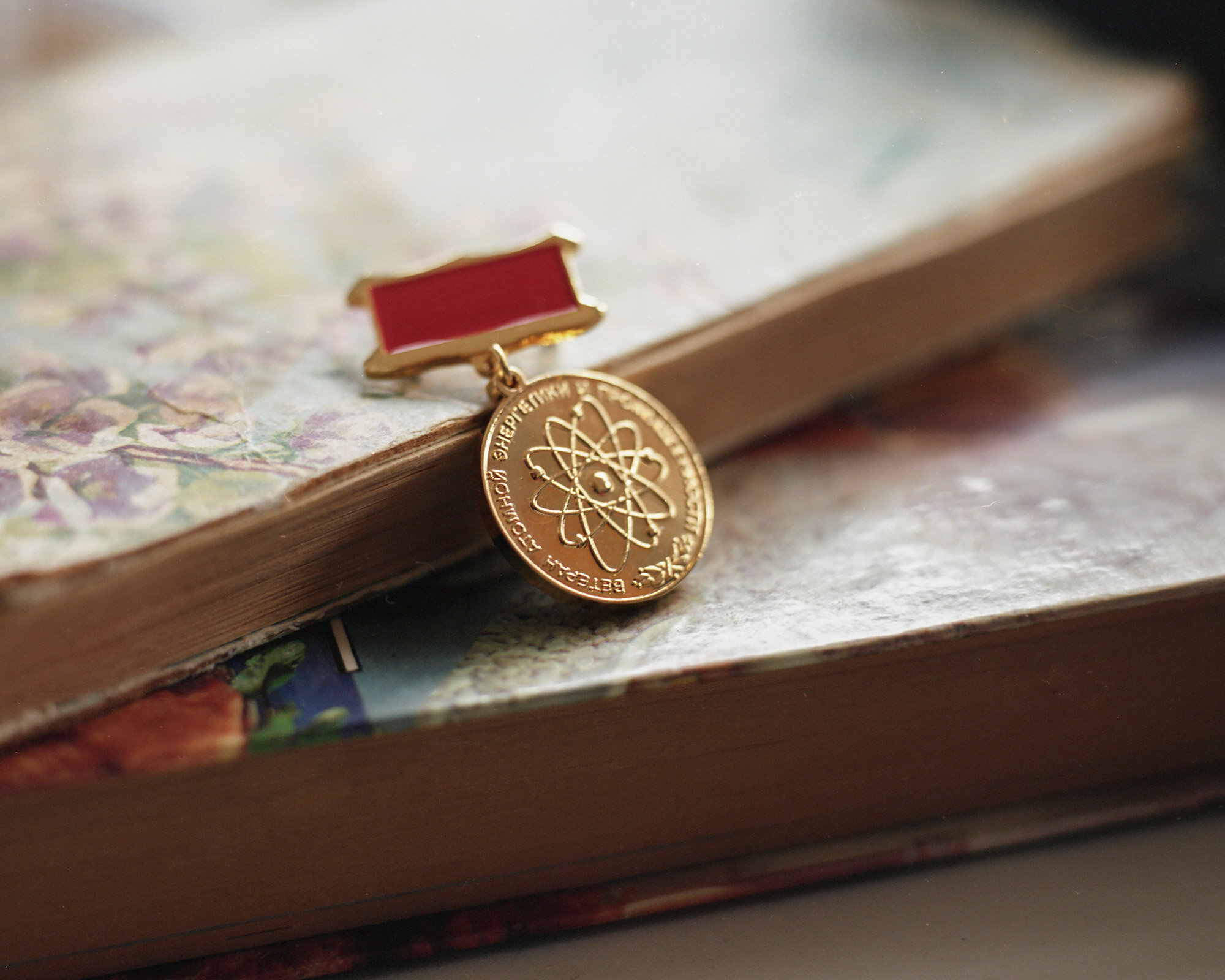

Arriving in 1975 from Nizhny Tagil, a city near the Ural Mountains, my grandparents were recruited to be a part of one such community – known as Maibox44. My grandfather moved first to start work, and the rest of the family – my grandmother, and their two children – followed six months later in the hope of a better life. “There were sports events, artists, and a theatre,” my grandmother Nadezhda told me. “I came here in 1975 and there were one- or two-storey houses, many barracks. The food and accommodation were free.”

When they arrived, my grandparents were allocated a two-bedroom apartment in a five-storey block that had a shared courtyard and playground. It was a drastic change to their way of life: they had previously spent eight years in a communal flat, sharing one room between the four of them. Now, their new home was set among trees and there were schools nearby for their children, including my mother who was five at the time. “There was a sense of beauty,” she told me, recalling early memories of their new home. “I did not get this feeling from the city that I came from. The buildings and houses were new. I remember thinking it was so beautiful. There were carefully placed flowerbeds.” My grandparents lived in this apartment until 2018.

“There was a sense of beauty. I did not get this feeling from the city that I came from. The buildings and houses were new. I remember thinking it was so beautiful. There were carefully placed flowerbeds. The residential architecture was built to accommodate a courtyard and playground for two opposite houses, our classes in school were then formed from these two houses and after school we played. The forest was near, there was a lot of nature. Each area was built with the intention to fulfil people’s requirements for daily life. In the summer we did athletics in the stadium; I took part in all competitions in school with my team. In the summer we went to compete all over Russia. I was the champion in the sixty metre sprint.”

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the function of closed towns has changed. Their existence has now been acknowledged, but the walls remain in place and a propusk (permit) is still required to access most towns, restricting entry for the wider public. They remain strictly off limits to foreign citizens without special permission.

“Mailbox44” is an exploration of my grandparent’s town, documenting three generations living behind the wall and the idea of Soviet “closedness” that it continues to create. For the oldest generation, the perimeter wall remains a symbol not just of protection from the perceived dangers of the world beyond, but also of the exclusivity of the lifestyle they once enjoyed, and their preferential treatment within the broader spectrum of Soviet society. “The town amazed us with its beauty, its was perfectly clean, quiet and cosy. It was interesting to live and work here,” my grandmother said. “Our children and grandchildren grew up in this town. My husband and I celebrated our golden wedding anniversary. Life continues.”

But a sustained lack of investment has meant there are now few opportunities and little satisfactory employment on offer. Many of the town’s younger people are leaving in search of a different life elsewhere – and are unlikely to return. “I didn’t feel any closure when I was a kid,” Ilya told me. “We weren’t allowed to understand that we were in a closed town … we felt normal. There is a feeling of limitation though. You feel the walls here, you understand there isn’t much space, you understand that the borders themselves are smaller. Sometimes I want to get out of here, sometimes I feel that I am cut off from the world. I want to think that I am not in a closed town because this status is not elite. I want to leave.”

“Our youth leave, but in their place come others from neighbouring small towns or villages ... for them it’s a chance to get into this town. The older generation are proud of their town, they have lived here ever since it was first established. They were young, energetic; they had families – this town is their whole life. The new generation already perceives reality differently. They understand that the towns affluence has changed. It’s a different world because there is little work, and this relates to the town’s closed status.”

Good journalism costs money

Please support us by buying a magazine

In the mountains of northern Albania, the “shepherds life” is little-known – and a long way from the romanticised ideal.

There are 800,000 informal and unpaid caregivers in Portugal, but their work is largely hidden and their stories untold. Photographer Teresa Nunes’ mother is one of them.

Emma Ringqvist sailed the Atlantic Ocean alone for nine months, including sixty-seven days where she was completely out of reach of both land and people. It was the purest experience of loneliness.

Calais has become synonymous with some of the most controversial aspects of the "refugee crisis". Now efforts to rebuild a troubled tourism industry are underway – but not everyone agrees on the direction.